SEYMOUR HERSH

Substack Paywall Subscriber

January 3, 2025

NOTE: I arrived in the US in 1977, the first year of Jimmy Carter’s administration. The press referred to the 39th President as “Jimmy" but his full name was James Earl Carter Jnr named after his father. The Carter family fortune was in peanuts, a major crop in Georgia. He had a not-so-bright brother Billy who created a furor when he accepted a $2million “retainer” from Libya because he was the President’s brother (an unregistered foreign agent, a major “no-no” in the US), dying at the age of 51. Jimmy Carter lived a full life to 100 beating many of his successors. Sy has all the goods below.

JIMMY CARTER’S MIXED LEGACY

As an ex-president he sought peace but in office he was an instinctive hawk

SEYMOUR HERSH

JAN 03, 2025

∙ PAID

I’m a working-class kid from the South Side of Chicago, and I helped my mother survive in the 1950s after my chain-smoking immigrant father died of lung cancer. My father ran a laundry and cleaning store in the heart of the African-American neighborhood, and most of his clients had come to the big city in the north from the Deep South.

I learned a lot about Georgia in particular from a young employee named Sterling who pressed pants and suits in our shop and took me on more than a few Sundays to Negro league baseball games at Comiskey Park that took place every other Sunday when the White Sox played away games. I was too young to share the beers, which were used to top off swigs of whiskey, but old enough to get a sense of their enormous relief at getting out from the tyranny of Jim Crow in the Deep South.

Sterling was always telling me I would be OK, essentially because I was not afraid to work hard and, most importantly, I had white skin. There was no malice in the comment: it was just a fact of life. A few years went by, and my mother decided it was time to go live with my brother in California, and there was no need for me to keep running my father’s vaguely profitable business. She left, and I pisssed her off by immediately giving the keys to the store to the employees, including Sterling, and I moved on. I reminded them to pay the rent, and I fled to the University of Chicago, where I was attending classes when I could, and moved into a $12-a-week basement room, with a bathroom down the hall—a life of sheer bliss. This was in 1958.

I graduated from Chicago with a degree in History and English and, after not finding a good job, decided at the last minute to ğo to law school there. I did OK for a few quarters but burnt out. Then I bummed around for a year or so and did my mandatory Army service, and found my way by sheer luck into the newspaper business. By the fall of 1969, I had worked a decade as a wire service reporter for United Press International in South Dakota and then for the Associated Press in Chicago and Washington, where I spent a few years covering the Pentagon and the Vietnam War. I worked hard and did a lot of good stories—some of them implicating Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and his staff as liars. I also stalked the Pentagon cafeterias looking for junior officers back from the war at lunch and did all I could to get them to tell me about their tours. It was understood that what was said there stayed there.

I learned a lot about body counts and useless killings but was bounced out of my Pentagon assignment after a series of negative stories about Vietnam, at the request, so I learned, of senior Pentagon management. By 1969 I’d left the AP and was freelancing, when I got a tip about a massacre in South Vietnam. In Washington I found out that dozens of Vietnamese civilians had been massacred in a village called My Lai, in March 1968.

The fall guy—there’s always a rotten apple when the military needs one—was Second Lieutenant William Calley, whom the Army would accuse—at the time, this was the gravest of secrets—of the premeditated murder at My Lai of 109 “Oriental human beings.” I got a copy of the official charge sheet. I wrote a series of articles about Calley and the massacre. Calley’s trial was held in 1971 at a military base in Georgia. On March 29, he was found guilty of the murder of 22 Vietnamese civilians. I was well into a book on the story with Bob Loomis, an editor at Random House, and I knew from my interviews with returning My Lai veterans, including one with Calley, that the US Army was up, as we used to say in Chicago, “shit’s creek” if it thought it was going to get away with the farce.

Enter Jimmy Carter, the governor of Georgia—make that, as I was learning, the very ambitious governor of Georgia. He pronounced Calley a scapegoat. Calley’s conviction, he said, was “a blow to troop morale.”

By this time, I had already published my book on My Lai and spent months giving speeches about the massacre and the war at colleges and universities all over America, but not in Georgia or elsewhere in the Deep South. I was beginning a quest that continues today—asking: Why My Lai and why was it covered up? I would learn that killings were reported, via South Vietnamese channels, and CIA channels, to the American high command in Saigon, and were known within a day to the staff of General William Westmoreland, the man in charge of the war.

You can call it an obsession, but it was a great story that gave me grave reservations about Carter, especially when he told an African-American church in Indianapolis in May, 1976, during his long-shot campaign for the presidency, that the Vietnam War was racist because the United States was fighting people of yellow skin and “we did not regret their deaths as much” as we would if they had been white. The pastor of the church later told the press that “Jimmy Carter has got soul.”

Carter’s comments came up at a later news conference and, as recorded by Charley Mohr, who spent years reporting from Vietnam for the New York Times, he denied that he had ever supported Calley or condoned his actions. He explained that he had never thought Calley was anything but “guilty”: “I never felt any attitude toward Calley except abhorrence. And I thought he should be punished, and I still do.” But the candidate said that he also thought that “it was not right to equate what Calley did with what other Americans were doing in Vietnam.”

Mohr quoted from a 1971 report in the Atlanta Constitution revealing that Carter had proclaimed the Monday following Calley’s court martial conviction to be “America’s Fighting Men’s Day.” He asked the citizens of the state, Mohr wrote, “to display the American flag and to drive with their headlights on to show their complete support for our servicemen, concern for our country and rededication to the principles which have made our country great.”

Carter was a weak president and more of instinctive hawk than he let on. After winning the presidency he named Cyrus Vance, who had been McNamara’s deputy and fellow liar about the Vietnam War, as his secretary of state. His secretary of defense was Harold Brown, who has served as President Lyndon Johnson’s secretary of the Air Force from 1965 to the swearing in of Richard Nixon in January of 1969 with no known complaints as Johnson intensified the bombing of North Vietnam and consistently refused to respond to North Vietnam, which was willing to discuss an end to the war but only after a bombing pause. Johnson refused to authorize the pause that he thought, so I would learn years later, would be a sign of weakness.

The Carter years came after Daniel Ellsberg’s revelation in 1971 of the Pentagon Papers that told in chilling detail how rational, intelligent senior officials—men with the probity of McNamara, Vance, and Brown—lied to the American people and the world about what was really going in the Vietnam War. The deaths of ours, and others, were a lesser consideration. McNamara would later publish a memoir in which he noted that he knew the war was lost by 1965 but could not bring himself to share that knowledge with the American people.

I continued to work as an investigative reporter for the New York Times, focusing on organized crime and corporate wrongdoing until 1979, when I left to begin a book on Henry Kissinger. But I continued to write occasional front-page stories for the paper, then edited by Abe Rosenthal, with whom I had an extraordinary relationship, for the next five years. I always had contacts in important places in the intelligence and military community, and after Carter’s death I asked a senior official what it was like being on the inside in the Carter presidency.

He was someone who had reason to attend many high-level White House meetings dealing with military, strategic, and intelligence issues during Carter’s four years in office. He told me he thought Jimmy Carter’s years in the Naval Academy and his subsequent active-duty service working with Admiral Hyman Rickover, the eccentric submariner who is credited with developing the Navy’s first nuclear-powered submarine, had limited his view of the world. Rickover was renowned for interviewing most Navy Academy grads who wanted to serve in the submarine command and being arbitrary, at worst, and demanding, at best, of those he selected.

He concluded early on, he told me, that Carter was “a naïve Academy grad. Never understood DC politics or real-world hard-ass power struggles. Strategic issues were a complete mystery. Rickover was his ideal of a military leader: the perfect nerd. Technically a wizard but a self-important ineffective arrogant leader.” In his view, Jimmy Carter had many of Rickover’s worst attributes, “hiding behind a fundamental religious piety for the poor and downtrodden. Calley was in his view just doing his best to follow orders.”

At one point, the senior official said, he challenged the president on that view, and told him that a secret Pentagon working group on Vietnam war crimes a few years earlier uncovered seven other massacres—none at the My Lai level—that were never prosecuted. The president’s response was that “bad things happen every now and then in war. Our senior Army leaders like General Westmoreland”—who ran the war from 1964 to 1968 and later served as the Army Chief of Staff—“are hardly to blame for a few bad apples like Calley.” History may provide a much more caustic assessment of the responsibility of the generals who ran a war that murdered millions of Vietnamese innocents.

These recent words, which came a few days after Carter’s death, among many glowing newspaper obituaries that focused on the often extraordinary good works Carter did after leaving office, are the words of an old Vietnam combat hand who, like me, has been unable to come to terms with the American lack of respect for the Vietnamese civilians whose slaughter should ever be a black mark on the US.

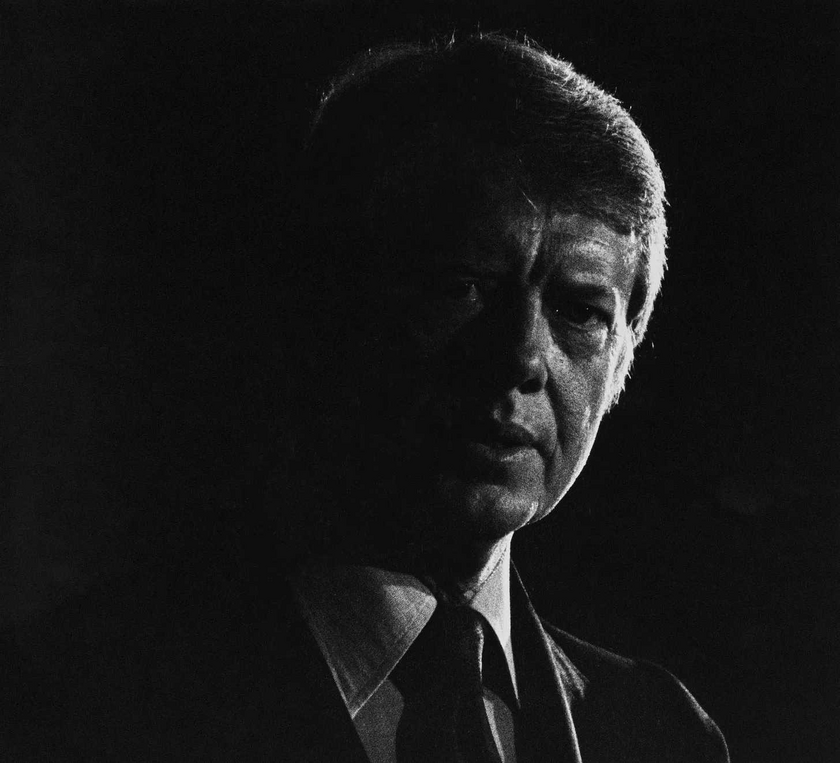

Photo:

Jimmy Carter addresses the 58th American Legion Convention in Seattle, on August 24, 1976. Carter used his address to announce that he supported a pardon for those who evaded the Vietnam War draft. / Photo by Jay Lurie/FPG/Archive Photos/Getty

https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd2029d61-dcad-438d-af18-f9e7d0207a01_4920x4472.jpeg